In my experience, most things on this planet come with an ending.

I find that there is often some resistance within myself to prevent natural completions, terminations or transitions even though I am conscious that everything and everyone has an end, at least in this physical manifestation.

Sometimes it is holding on to a job simply because I don’t want to accept it is over or deal with the fact that I’m no longer stimulated or challenged by it.

Sometimes it is gripping hard to a relationship that has long served its purpose and only exists because I, or we, keep pumping life into it in fear of the alternatives or in laziness based on what is comfortable and familiar.

Then, there is the obvious and biggest example of this. Death. Yes, death. The big one. The end of ends. The Grand Farewell.

In my work and in my own experience, I find that our anxiety with regard to our own physical termination has a great deal to do with many of our often times silly obsessions, patterns and hang-ups. What is most notable, however, is that our anxiety about death tends to be largely unconscious as most of us simply do not wish to think about it let alone discuss it with others, lest we make it ever more real.

So, what are we so worried about? There are of course the obvious questions such as will it hurt… will we be scared when the plug is pulled… will our loved ones miss us…will we be judged for things we messed up while alive?

For some, adherence to particular spiritual or religious doctrines helps place death within the specific context of our belief system. Our cosmology, the map we create and nest in that explains our universe and extrapolates for us beyond the flat line, seems easier for those who believe in a clearly defined religion as most theologies inherently answer the matter of life and death as one of the foundational purposes.

Which brings me to my dog.

Chaco is now 15 ½ years old. He wobbles and hobbles, pees and poops wherever it moves him, eats when he feels like it and only that which appeals to him at the moment. We have to hide his incontinence pills in balls of Wonder Bread and cream cheese, otherwise, no go.

Chaco is now 15 ½ years old. He wobbles and hobbles, pees and poops wherever it moves him, eats when he feels like it and only that which appeals to him at the moment. We have to hide his incontinence pills in balls of Wonder Bread and cream cheese, otherwise, no go.

He stares at himself in the mirror for long periods of time as if lost in the picture of who he has become. He spends several hours in a day standing at my side, staring into my eyes, panting.

He is, by all intents and purposes, nearing the end of his dog life.

Some folks would have “put him down” by now, claiming it is just “humane.” Others discuss the notion of “quality of life,” asking questions about his ability to run and play, making assertions that a dog that can not catch a Frisbee any longer may not be in possession of a good enough quality of life.

However, Chaco lives.

I’m not sure if he enjoys a particular cosmology, if he is conscious of a life after death or if he believes he will just “STOP” when the ride ends.

I do know, that he melts when we pet him. I know that he loves some good wet food and tuna fish makes his heart sing. I know that there is still a gentle skip in his gait when we get to the dog park, even though he stumbles around and makes his mark by sometimes lifting the wrong leg. I know that my best friend for over 15 years, though mostly deaf, always knows when I am leaving for work and makes his way to the front door to peer his sweet head around and wish me a good day.

I know that Chaco is not finished with this life. I am basing this belief on the sense that he will let me know when it is no longer worth it. I am basing this on 15 years of history together that has proven that my dog communicates his needs pretty darn well.

And, I suppose, I’m basing this on my own cosmology. The way I perceive life and death is the way I move through my existence, making decisions and choosing paths along the journey. I believe that Chaco contracted with me long ago to walk this walk together, to enjoy the journey for as long as we decided it was working for us both. It’s a relationship, after all.

And relationships are a two way street.

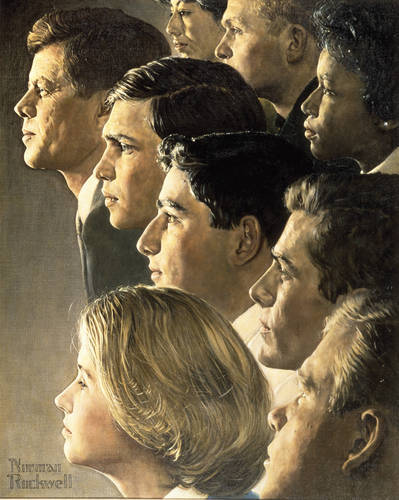

I hope that more people take the notion of socially conscious “paladinism” seriously as we move farther down the road of personal responsibility when it comes to finance, education, spirituality, and so forth. When a tragedy like the one this month in Tucson serves more to separate the “parts” of our democracy rather than unite us, I fear that there is nowhere near enough “praying with our legs” happening in our great nation.

I hope that more people take the notion of socially conscious “paladinism” seriously as we move farther down the road of personal responsibility when it comes to finance, education, spirituality, and so forth. When a tragedy like the one this month in Tucson serves more to separate the “parts” of our democracy rather than unite us, I fear that there is nowhere near enough “praying with our legs” happening in our great nation.

Jeffrey Sumber is changing the world, one relationship at a time. For over two decades, Jeffrey has worked to understand the human experience from as many angles as possible. As a successful psychotherapist, marriage counselor, and life coach, Jeffrey has worked with thousands of clients who strive to live their best lives.

Jeffrey Sumber is changing the world, one relationship at a time. For over two decades, Jeffrey has worked to understand the human experience from as many angles as possible. As a successful psychotherapist, marriage counselor, and life coach, Jeffrey has worked with thousands of clients who strive to live their best lives.